The producers—the "Suits" with their clipboards and permits—they stood there looking at the mess, and they didn't see the problem. To them, cardboard is cardboard. They saw volume. They thought, "Pile it up, it’ll be soft."

But Ferdi saw the void. He knew that if you mix box sizes, you create uneven density. You create air pockets. If he hit a pocket of small boxes next to big ones, he wouldn't decelerate smoothly. He would torque. The kinetic energy would snap his neck. Or worse, he would punch right through the stack like a 180-pound bullet and hit the hard deck.

And the deck down there? That’s limestone. That’s the planet. The planet is undefeated. It has a record of about a hundred billion and zero against human bodies.

Ferdi cracked a Monster Energy. The can popped like a rifle bolt in the quiet quarry. He took a swig of that battery acid, and he just stared at the mess.

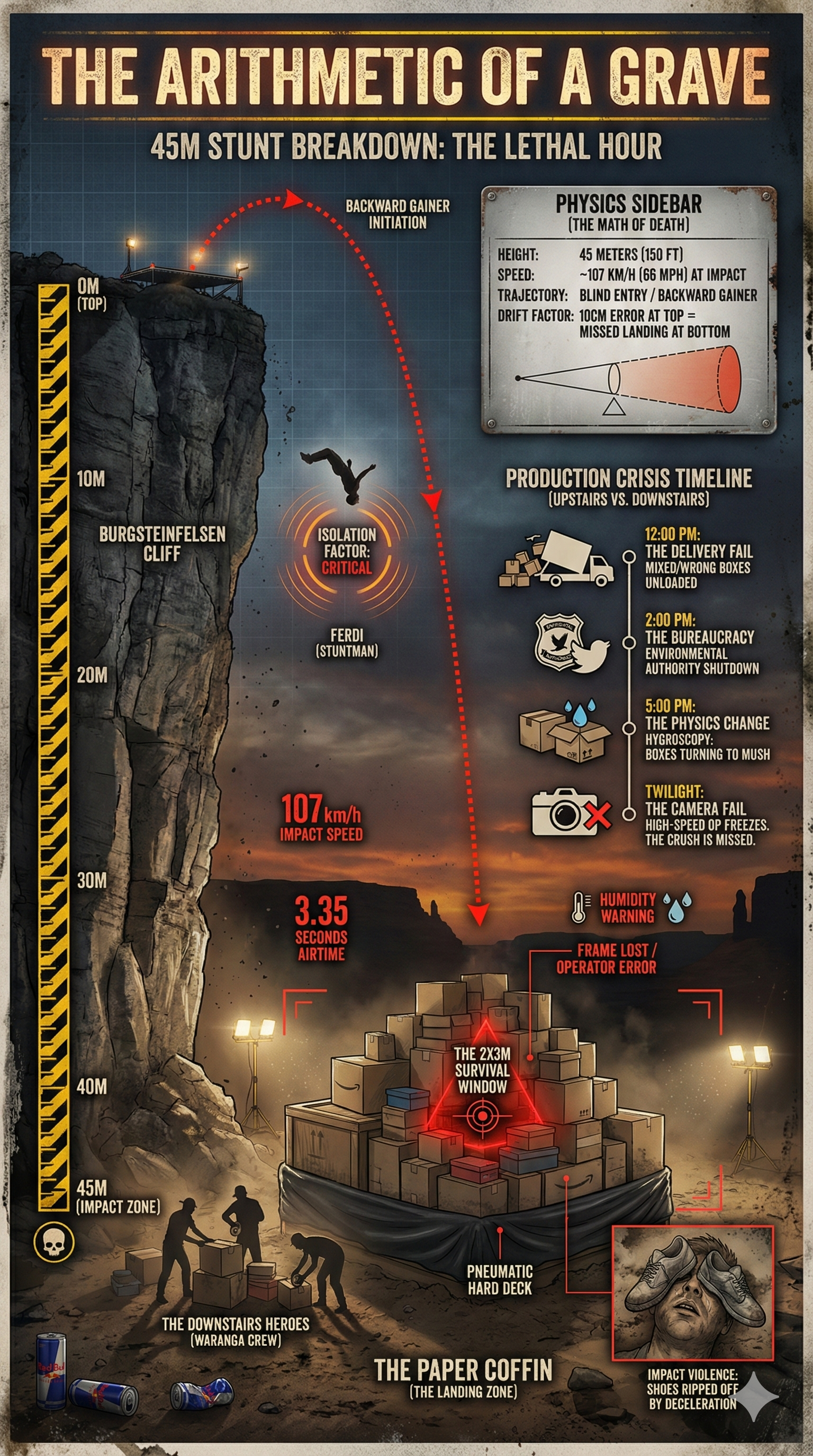

He was doing the recalculations in his head. He realized he had to narrow the landing zone. He had to build a "pyramid" in the center—a kill zone of perfect density, maybe two meters by three meters wide. That was the target.

From 150 feet up, a two-by-three-meter target looks like a postage stamp.

And here is where the math gets mean: Drift.

If he pushed off just 10 centimeters too far to the right at the top—a micro-muscle twitch—geometry amplifies that error over a 45-meter descent. By the time he reached the bottom, that 10 centimeters would become meters. He would miss the pyramid. He would hit the trash. He would die.

He looked at his team. These weren’t Hollywood union riggers with craft services and overtime. These were his boys. They worked with him at a bar called Waranga in Stuttgart. Ferdi wasn't the boss there; he was a runner. He was the guy hauling crates of glass, wiping down sticky tables, sweating through the shift until 4 a.m. Just hard, physical labor.

They looked at the pile of garbage cardboard. They looked at the slope of the terrain, which wasn't even flat. They looked at Ferdi.

One of them asked, "Do we scrub?"

Any sane man would say yes. Any man who loved his life more than his reputation would say yes.

Ferdi finished the Monster. He crushed the can and tossed it.

He said, "We don't scrub. We build the pyramid. We put the good boxes in the center. We use the trash for the perimeter. We make it work."

It wasn't bravery. Bravery is for people who don't know the odds. This was arrogance. Beautiful, professional, suicidal arrogance.

He looked at the producer and said, "Start unloading. And don’t drop a single one. We need every inch of air we can steal."

And so they started building a coffin out of paper, hoping to God it would act like a feather bed.